Are dynamic accumulators a garden myth?

I was listening to episode 444 of the excellent Joe Gardener Show when the guest brought up so-called dynamic accumulators. She mentioned them in the context of permaculture, and repeated the conventional wisdom about using tap rooted plants such as comfrey to pull nutrients up from deep in the soil.

The guest was Brandy Hall from Shades of Green Permaculture. Here's what she said.

Dynamic accumulation. That's a term that's really popular in permaculture. Deep taprooted plants that pull nutrients up, assuming the nutrients are in the soil. You know they aren't pulling them from thin air. Pulling what's there up into their leaves. Those leaves die in the winter and then those nutrients are released into the upper horizons of the soil.

It's hard for me to hear about dynamic accumulators from experts because to me, dynamic accumulators seem like the gardening equivalent of bigfoot. They are much talked about, but when you try to examine them, they disappear.

The concept of dynamic accumulators feels a little thin to me, so in this blog post I'm going to try to pin them down and see what sticks.

Defining dynamic accumulators is hard

The big problem with dynamic accumulators is that they have no scientific definition. Some people say that they are plants that pull nutrients from the soil and store them in the leaves. Other people tie the concept to tap roots. They say that dynamic accumulators pull nutrients from deep in the soil and bring them to the surface.

Unfortunately, these ideas are both flawed to my understanding.

All plants pull nutrients from the soil and move them into their bodies. That's basically the definition of a plant. Plants use sunlight to combine water with nutrients in the soil to make sugars and other nutrients that they store in their bodies and give away in the soil food web. Every single plant does this, so the concept is meaningless as a distinction.

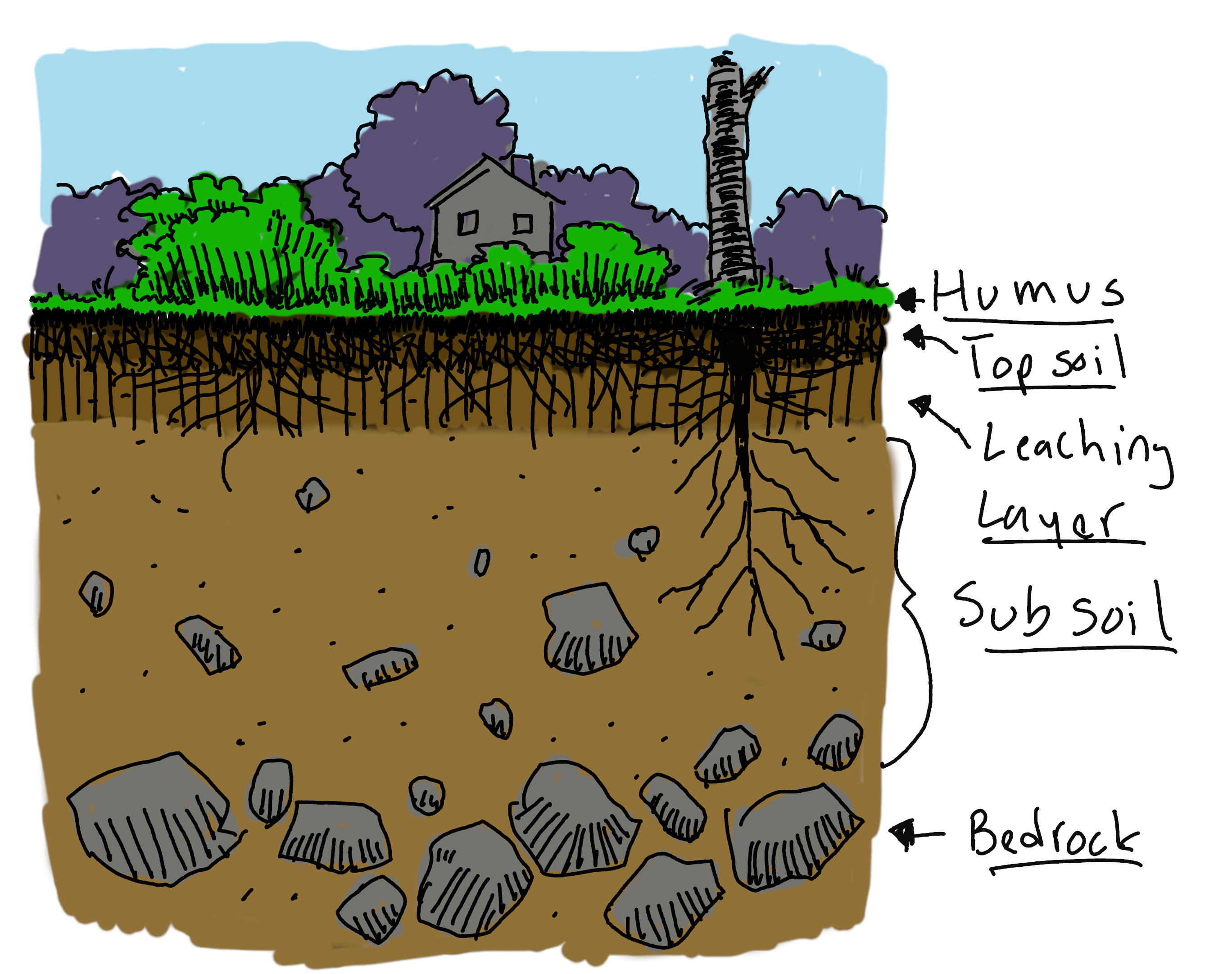

And the idea that tap roots pull nutrients up from deep in the soil doesn't make much sense to me either. The vast majority of nutrients in the soil are in the top few layers of soil. The nutrients are in the organic matter in the humus and the topsoil.

It makes no evolutionary sense for a plant to send a deep tap root into the soil with the fewest nutrients. It would be much better off sending fibrous roots into the top few layers of soil.

So if dynamic accumulators don't stand up to my own critical thinking, how are they being discussed by professionals and scientists?

What does science say about dynamic accumulators?

The best overview of the topic of dynamic accumulators that I've found is Breaking Ground with Dynamic Accumulators by Greta Zarro. She points out that practically everything we think we know about dynamic accumulators is indeed anecdotal. It's not based on evidence.

But she also points out that this is beginning to change in some interesting ways.

For instance, there's an effort to pin down a scientific definition of what qualifies as a dynamic accumulator in reference to existing classifications of plants that remove specific things from soil.

While dynamic accumulators are used to gather beneficial nutrients from the soil, hyperaccumulators are used to gather toxic heavy metals. When used for soil remediation, the plant tissue of hyperaccumulators is harvested and removed from the site. To qualify as a hyperaccumulator, a plant must accumulate metals above established threshold concentrations: 100ppm (for Cd), 1,000ppm (for Co, Cu, Ni, As, and Se), and 10,000ppm (for Zn and Mn). Brown suggests that similar thresholds should be set for dynamic accumulators, in ppm, using dried plant tissue samples, consistent with hyperaccumulator thresholds.

She points to work by Brown and Kourik that goes even further.

Kourik suggested that dynamic accumulators should demonstrate high amounts of nutrient accumulation, as compared to other plants. To address this, we started by setting the thresholds at 200% of nutrient value averages, which results in about 10.40% of plants qualifying in each nutrient category. However, for this model to endure, the thresholds need to be fixed at specific values rather than remain relative to the averages, because those averages will change over time as new plants are added to the databases. So we rounded off the thresholds and set them at even numbers, still roughly 200% of the averages, representing the top 10.08% of plants.

And since that article is from 2020, we can now look at the results of the author's two year study of dynamic accumulators.

Unfortunately, the results aren't quite clear. While it's true that some of the plants they studied were indeed able to accumulate higher concentrations of some nutrients, these levels were almost always in proportion to what was already in the soil. It was very rare that plants were able to accumulate high levels of specific nutrients in poor soil.

Perhaps most importantly, we found that plant tissue nutrient concentrations are relative to soil nutrient concentrations. Dynamic accumulators are well-suited to extract specific nutrients from fertile soil, but they aren’t going to create nutrition that isn’t there...That said, even when grown in poor, unamended soil, two species surpassed dynamic accumulator thresholds. Dried lambsquarters foliage was found to possess potassium concentrations that exceeded dynamic accumulator thresholds (40,715 ppm), and liquid fertilizer made by steeping lambsquarters foliage in water for 5 days contained the highest potassium concentrations of all the trial crops (903 ppm)... Likewise, Russian comfrey foliage surpassed dynamic accumulator threshold concentrations for both potassium (52,959 ppm) and silicon (513 ppm), with similarly high potassium concentrations found in the resulting liquid fertilizer (889 ppm).

They also found that stinging nettle made particularly good fertilizer, both in a liquid form, and when chopped and dropped directly onto the soil.

We found stinging nettle foliage to possess the highest calcium concentration of all trial crops... Liquid fertilizer derived from stinging nettle foliage proved to be very nutrient rich, possessing the highest concentrations of P, B, Ca, Cu, and Mn after 5 days of steeping compared to all other trial crops, as well as the highest nutrient carryover rates for all of these nutrients plus K and Mg, meaning stinging nettle’s nutrients are particularly soluble and well suited for liquid fertilizer.

The results with stinging nettle were consistent with the idea that dynamic accumulators are pulling nutrients up from the subsoil.

Chopping and dropping with stinging nettle also produced some exciting results. Calcium concentrations more than doubled in the 0-6” and 6-12” soil horizons, while dropping to 63% in the 12-24” soil horizon. This is consistent with the widely held belief that dynamic accumulators enrich the topsoil by extracting nutrients from the subsoil.

Dynamic accumulators sound a lot like...

But science isn't driven by one study or one scientist. Science builds a picture of the truth by combining the work of many scientists and many different experiments. While these initial experiments show some interesting results that seem to lend credence to some of what permaculturists have been saying for years, the studies are far from conclusive.

And what does this work even say?

It says that dynamic accumulators are plants that are particularly good at absorbing some specific nutrients from the soil, and if you chop and drop those plants then you can increase the amount of those nutrients available in your top soil.

So the question I want to leave you with is this: How are dynamic accumulators any different from cover crops? How is chopping and dropping comfrey or stinging nettle much different from chopping and dropping buckwheat or some other cover crop? The particular selection of nutrients may be different, but otherwise it seems pretty similar.

In the beginning of this post, I said that dynamic accumulators were a garden myth because when you examine them, they seem to disappear. That seems to have occurred again here. We looked at the latest study on dynamic accumulators, and the findings of that study essentially say that dynamic accumulators are the same thing as cover crops.

I'll leave it up to you to decide whether you want to cling to the concept of dynamic accumulators as used in the permaculture literature. For me, dynamic accumulators still seem like little more than a buzz word.