How I use radishes from my garden: Honey radish ramen

Before we get into this, I need to tell you that I am not a cook in any fashion. My wife does 99% of the cooking in our house. I generally only cook for myself.

I am a gardener, and I don't like to let the food I grow go to waste. This becomes a conundrum in summer when we are harvesting more vegetables than we can immediately use, but it's also an issue in winter when harvesting vegetables that not everyone in the family enjoys. In winter in California there are two vegetables that I am typically harvesting: lettuce and radishes.

Lettuce is extremely easy to use. Throw it in a salad, put it on a sandwich, etcetera.

Radishes, on the other hand, are something of an enigma. They taste pretty awful raw. The leaves have sharp spines, and the body of the radish has a peppery flavor that can be overwhelming.

This recipe was born out of my desire to find a pleasant way to eat a lot of radishes. I like to make it for lunch on chilly days when there are radishes to harvest in the back yard.

Ingredients

You can use any type of radish for this recipe. I usually use Daikon radishes because I grow a lot of them and the leaves are bigger than on red radishes, but the red radishes will work fine. If you are using red radishes then you might want to use two of them.

- 1 radish

- 1 container of chicken ramen

- 1 tablespoon of honey

- 1 teaspoon of garlic powder (or 1 clove of fresh garlic, chopped)

Recipe

As I said at the beginning of this post, I am not a cook. So this recipe is pretty simple.

- Chop up the leafy parts of 4 or 5 radish leaves. Do not use the leafless stems.

- Chop up the soft, white middle section of a small daikon radish. Only use as much as you want.

- Make ramen as usual, using boiling water and adding the spice packet.

- Add radish, radish greens, honey, and garlic to the bowl.

- Wait 1 minute to allow the leaves to cook down a bit (this softens the spines).

- Enjoy!

Easy to grow plants for beginner gardeners in California

If you're thinking of trying your hand at gardening for the first time in 2026, you might be wondering what plants are easy to grow in California. Which plants do well in our climate and which need more care? In this post I'm going to list three plants that are easy to grow in all of California. All three of these plants require minimal care to be successful, so they're great picks for beginner gardeners.

1. Sunflowers

My first suggestion is sunflowers. Sunflowers are beautiful and iconic all over the world. The bright yellow flower heads look so joyful as they tilt their heads to follow the sun through the sky. They are great accents in any yard, and the seeds are also edible. You can chop the flower head down when the seeds are ready to claim them for yourself, or just leave them there for the squirrels and the birds.

Growing sunflowers in California can be remarkably easy if you start them at the right time. If you start them in winter or early spring, then all you have to do is put the seed about an inch in the ground. When the rain falls it will trigger seed germination and by late spring you will have a beautiful tall sunflower.

If you wait until the rainy season has passed, then you may have to do a little more work. You can put a sunflower seed in some soil in a paper cup. Keep it moist for two weeks or so. When it is about six inches tall, you can transplant it into your yard.

Sunflowers develop thick taproots that gather moisture from deep in the soil, so they don't need much water. You probably want to water them every other day for the first few weeks while they are getting established. Then you can taper off the watering.

If you want to go the extra mile to support local wildlife, then you could even grow our native sunflowers. California Bush Sunflower doesn't grow the giant yellow heads on long green stalks that you see in more common sunflowers. Instead the flowers are about the diameter of an egg, and they grow in a bushy form. California Bush Sunflower makes a great thick hedge, and it blooms nearly all year long.

2. Cherry tomatoes

My second suggestion for a plant that's easy to grow for beginner gardeners in California is cherry tomatoes. Cherry tomatoes are the small, sweet tomatoes that are most often eaten in salads or on skewers. They are so delicious that even my kids pick them straight off the vines and eat them for snacks.

Cherry tomatoes are nice plants for beginners because they are easier to grow than standard full sized tomatoes. They are more disease resistant, they require less water, and they will re-seed themselves year after year.

You can start cherry tomatoes in containers or in the soil. In either case, just make sure to keep the soil moist for two weeks or so to allow the seed to germinate. When you put the plant in the ground, water it every other day until it starts bearing fruit, then you can taper off the water.

All tomatoes are vining plants. For cherry tomatoes, these vines usually form into a tangle that is more or less bush-like in form. These bushes can get quite large if you let them. You should trim them back freely once the bush reaches a size that you like that is over 3-5 feet tall and wide.

3. Blackberries

My third suggestion for a great plant for beginner gardeners in California is blackberries. Blackberries are another fruit that my kids will pick straight off the plant. What is better than seeing your kids eating healthy food out of the garden? And if you've seen the price of blackberries from the grocery store recently, then you know how much money you'll save by reserving a small section of your garden for blackberries.

Blackberries grow in two different forms: vining and caning. The caning varieties of blackberries grow on long canes sticking out of the ground. The vining varieties of blackberries grow on vines that run along the ground and form hedges over time. Both varieties typically have thorns, but humans have bred varieties of the caning blackberries that have very few or no thorns. Both the caning and vining blackberries produce nearly identical fruit.

The nice thing about the vining blackberry is that it's native to California. California blackberry grows natively in nearly all forests in California. It likes to grow as an understory plant beneath tree canopies. It's particularly common in forests of tall redwoods and towering douglas firs.

Growing the native blackberry is a good choice because it won't invade natural areas if it escapes your garden. Also, because it is native to California it is adapted to having water in the winter and little to no water in the summer. This makes caring for it even easier than caning blackberries, which will require more water and can become invasive if they escape your garden.

Sunflowers and tomatoes are annual plants. This means that their entire lifecycles occur in one year. Blackberries are perennial plants. This means that you put them in the ground once and they last for years. You should plant your blackberries in the winter or early spring. Then water them twice a week through the summer.

Weeds of California: Oxalis pes-caprae

One of the most common weeds in California gardens is Oxalis Pes-Caprae, aka Bermuda Buttercup. I usually refer to it by the name "Oxalis", but this is a really poor way to describe it because Oxalis is a genus of plants. There are many species of Oxalis, aka wood sorrels, that are native to California, such as Oxalis Oregana, aka Redwood Sorrel. Still, for the rest of this article I'm going to use the name Oxalis to refer only to the one I see most commonly in the garden: Oxalis pes-caprae.

Oxalis pes-caprae is an easy plant to love, despite it's weedy nature. It's edible, and has a pleasant sour flavor. Some foragers like to use it like lettuce in salads. It also puts on a beautiful display of small, vibrant yellow flowers. For this reason, the Oxalis bloom in the late winter can sometimes attract hikers and sightseers.

But looks can be deceiving. The California Invasive Plants Council (Cal-IPC) calls it a moderately invasive plant. If not controlled, then it has the potential to invade natural areas and displace native plants. I know that I've seen it taking over some of my favorite nature areas, such as the Bear Creek Redwoods Preserve. I'm grateful to the staff and volunteers who have kept it in control there.

Controlling Oxalis

When I first moved into my house, Oxalis was everywhere. It was in the front yard, it was in the back yard, and there was a carpet of Oxalis covering one of the side yards. Controlling it can be somewhat difficult. Even though it "does not produce seeds, it is difficult to control because of its ability to form many persistent bulbs". So I got to work weeding, and when I was lucky I pulled out an entire frond, with a bulb attached at the end.

If you don't manage to pull out the bulb, then Oxalis will come back year after year until it is exhausted. Still, it's a relatively easy weed to pull. I just pulled it whenever I saw it coming up each year for around three years, and now I rarely see it in my yard at all.

University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources notes that if wedding isn't effective, herbicides can be used to control Oxalis.

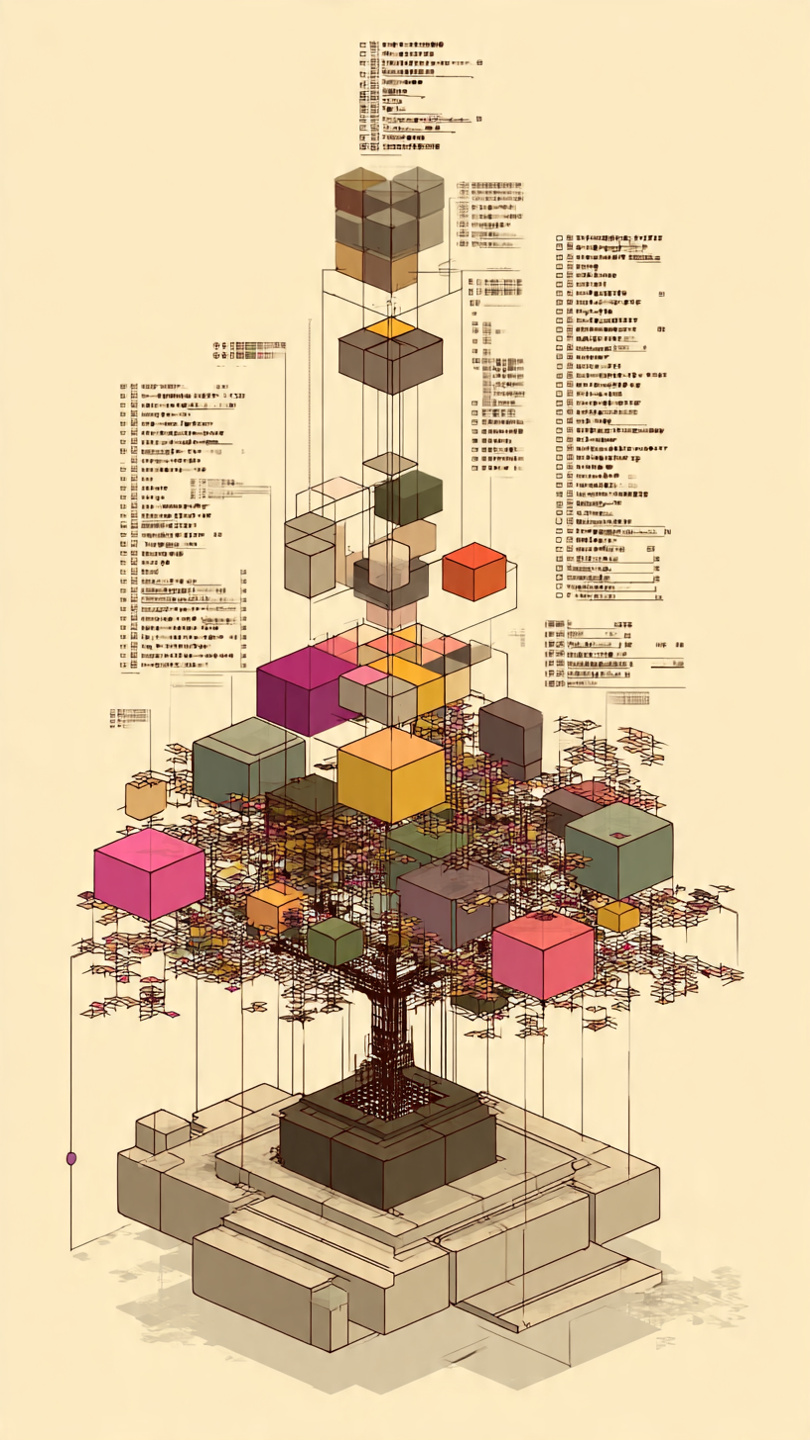

Caching: The most important topic in software development

I increasingly think that caching is the most crucial concept required to be a good software developer. Understanding caching is vital at the micro level of computer engineering, but it's also vital at the macro level of system design, and in the middle with software engineering. You really can't be a good software developer if you don't have a strong understanding of caching.

This is the third in a series of three articles about caching. I wrote one article about how caching is limiting the AI industry in a way that nobody is talking about. I wrote another article about how Spotify's failure to understand how and when to use caching is hurting the user experience of their app. This article will give you three reasons why a deep understanding of caching is one of the most important skills for a software developer to master.

SPOILER: It's because the data structures that underlie all caches are critical to everything that software developers do.

1. You cannot understand the web without understanding caching

How many layers of caching are involved in any web request?

Take a minute to think about it. It's not an easy question to answer. In fact, the correct answer is that it varies depending on context, however, it's generally at least three.

- All web browsers have at least one cache layer.

- Most websites use a Content Delivery Network (CDN) that caches static assets such as images.

- Most servers cache requests or pieces of requests.

And that is a simplified view of a very simple website with not many users. Once you get databases involved, you're almost certainly introducing another layer of caching. The web server will typically have one layer of caching around requests, or pieces or requests, and another layer of caching around database access.

The fact of the matter is that you can't understand how the web works without understanding the way the various standard layers of caching interact. Since almost any software you write is going to interact with the web in some way, a software developer has to have a basic understanding of web related caching in order to write effective software.

2. Misuse or underuse of caching is a common source of failure as systems are built or scaled

Using caching incorrectly, or not at all, is the most common source of failure when building or scaling a web service.

I was once at a company where they had a notification list for each user. They were struggling with the scalability of their website. They didn't understand why everything seemed to load so slowly, especially notifications. Well I asked how they were storing notifications and the answer was a search optimized database called ElasticSearch. ElasticSearch is a great tool ... for search. However, it has to re-index every document in the database every time a new one is added, and that's expensive. This is a failure to understand the way notifications should be stored or cached to make it fast for users to access them.

I was at an ecommerce company where list pages were slow. The problem was that the list pages had lots of parameters, and every time a parameter was changed the page had to hit the API to get a new list of items. Well, the items didn't change that much, and the parameters changed even more rarely. We figured out that it would be easier just to cache the list of every set of parameters for a given list page, and then the list pages loaded instantaneously. The difference was night and day.

The point is that almost all scaling problems can be solved by changing the way items are stored or cached.

3. Hash tables are crucial to software developer interviews

The final, crucial reason that all good software developers need a deep understanding of caching is that they need an understanding of caching to be hired in the first place. Questions about caching are critical to both coding problems and system design problems.

Most caches are implemented using a data structure called a Hash Table (aka Lookup table, dictionary, map, associative array). In almost every coding interview I've ever been part of (on either side), there has been a question that involved the use of a hash table. Some of the most frequently asked questions are based on hash tables: Two Sum, Ransom Note, and Top K Frequent Elements.

Caching is equally important to any system design interview. Whether you're designing Netflix, or a parking garage, or any other service, if you forget the cache layer, then you won't get the job.

Spotify has usability problems

I pay $19.99 per month for a family plan to use Spotify. It is the most expensive individual streaming service that I subscribe to, but I value it because I listen to a lot of music and a lot of podcasts, and I don't like it when they are interrupted by commercials.

But the Spotify app has had the same basic problems for years, and Spotify is either unaware of them, or lacks the software development expertise to address them. And these issues ruin the experience of using the app, especially for software developers like me who understand how easy it would be to mitigate them.

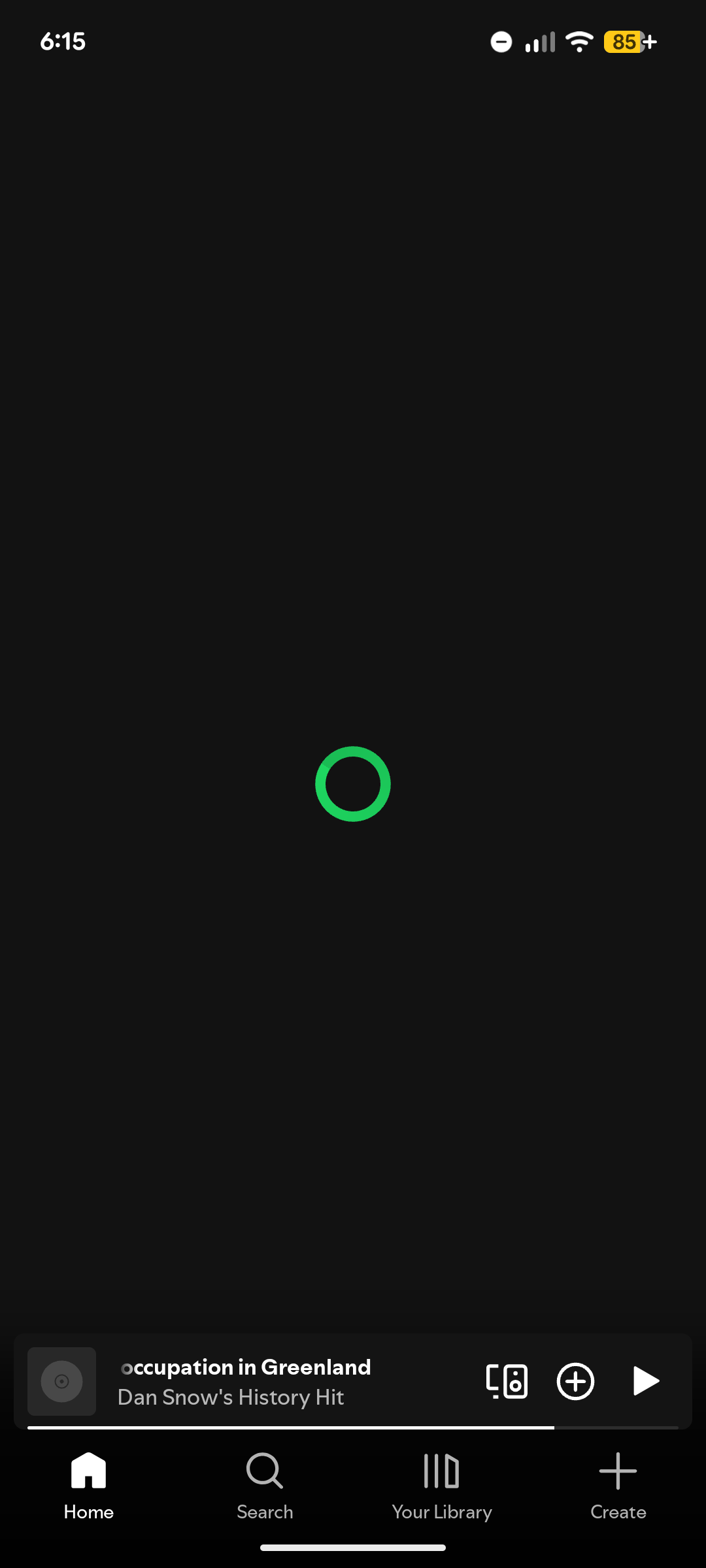

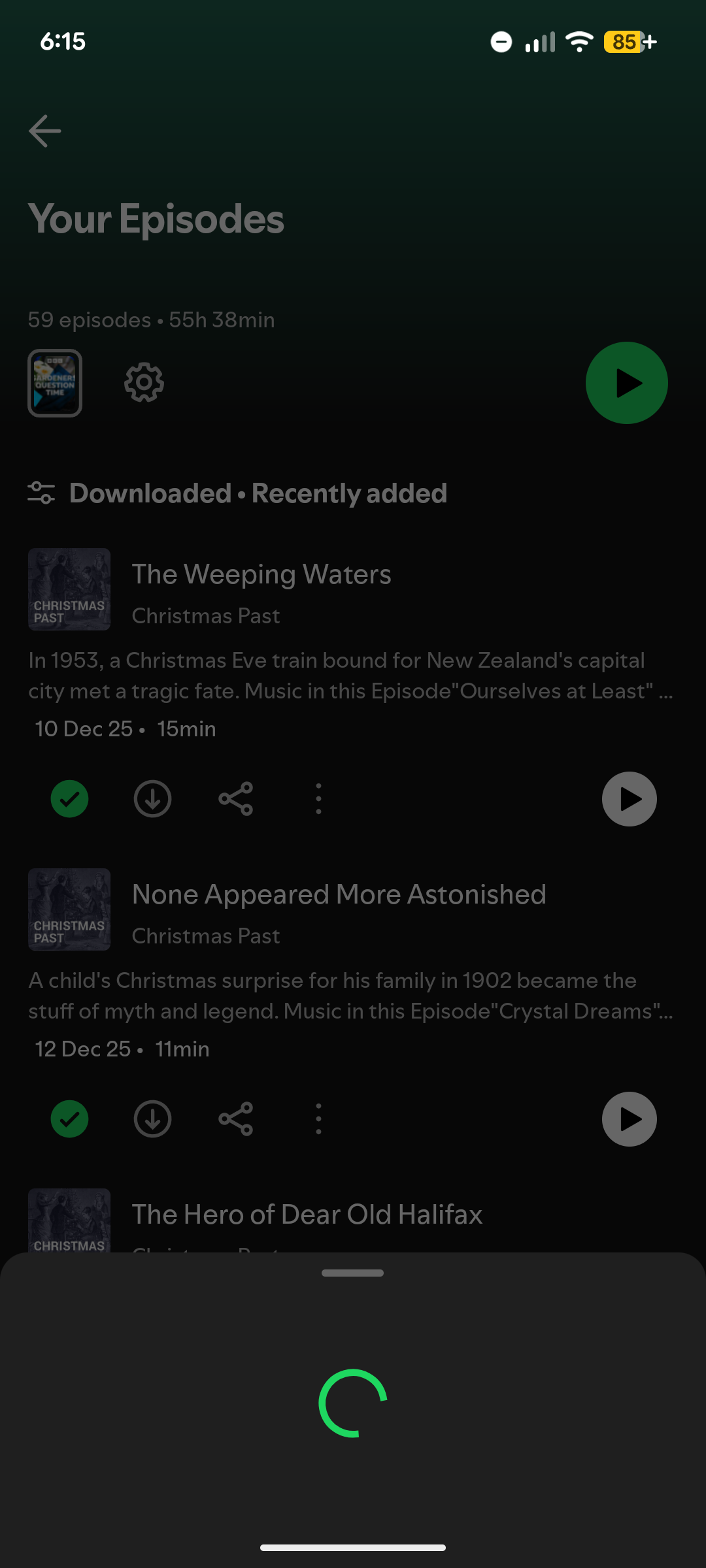

The first thing I usually do with Spotify when I open it is click Your Episodes. This is where the list of my podcast episodes that I've downloaded are displayed so I can listen. It's easily the most used page on the Spotify app for me, yet every time I click on it, I have to sit there and wait for a spinner that sometimes never ends.

What's frustrating about this is that it's so easily solved with a basic, widely used approach that could be Googled and implemented relatively quickly. And yet this issue has persisted for years.

All you have to do in this case is cache the list of "Your Episodes" every time you fetch it. This means saving a file to the phone with the list of episodes in it. Then, when a user clicks "Your Episodes", you read that list and show it immediately to the user while showing an indicator that you are fetching the full list.

This is a common approach on list pages for ecommerce and media sites. Usually, the user is seeking something from that list that was there last time they checked it. It's rare that they need the latest thing. So this algorithm instantly satisfies most users.

But that isn't even the most egregious case of this in the Spotify app: I dare you to try to add something to a playlist. The Spotify app shows a spinner and runs a web request when you try to open the three dots menu on a track.

Yes, it needs to hit the Spotify backend to show a menu.

This is embarrassing because not only is it strange to have to run a web request to get a menu, but it's strange that they aren't caching that menu. Even if customers see different menus, those customers can be grouped and the menus can be cached in some way.

The thing is, these usability issues aren't the only problems with Spotify as a whole. Spotify is notorious for not paying small artists, and Spotify pays artists less than Apple or Amazon.

So when you layer the usability issues on top of the structural issues with paying musicians, it's starting to become difficult for me to justify continuing to pay them $19.99 a month.

In closing, if anyone at Spotify sees this, let's talk: evanxmerz (at) yahoo (dot) com. This is a situation where it's so frustrating that I'd gladly solve it myself, or at least give the feedback to do so.

NOTE: I am a super user of music streaming services, so this is actually the third article like this that I've written. In 2016, I wrote a post about how Pandora makes discovery more difficult than I liked. In 2018, I wrote a somewhat similar article extolling the problems of using SoundCloud as a musician rather than a listener. Thanks for reading my opinions on music streamers. I used to be an Amazon Music subscriber, and I'll probably switch away from Spotify here soon, so I probably have a few more of these coming eventually.