My Electrification Budget

2023 was the hottest year in human history, and 2024 looks like it's going to be even hotter. This has everyone wondering what they can do to lower their carbon footprint.

If you're thinking about electrifying your life, then you aren't alone. Millions of people are starting to rid their lives of gas burning cars and appliances, and replacing them with safer, more efficient electric options.

Still, there are a lot of barriers to electrification, and budget confusion is a big one. In this post, I'm going to walk you through our electrification journey so you can get an idea of how much it cost for us, and maybe avoid some of the mistakes we made.

Small home lifestyle

We live in a small house. This was a choice partly dictated by where we live; Silicon Valley is one of the most expensive places in the world, so we could only afford a small house. But it's also something dictated by energy efficiency; it's much more energy efficient to only maintain as much house as you need.

Our house is 990 square feet. This makes it an especially good example for other people to look at. Round it up to 1000 square feet, then the math is easy for figuring out how electrifying your home might relate to ours.

Still, we live in one of the most expensive parts of the country, so you might want to divide by some cost of living. The 2023 median home price in San Jose was $1,100,000 million according to realtor.com. The median home price in the us for the same time was around $412,000. So you might reasonably divide this total in half for your area.

The total cost

These prices include the cost of installation, but they don't include rebates, and again, this is from one of the most expensive parts of the country. Also, we generally didn't purchase the cheapest of anything; we opted for the devices we wanted rather than the most affordable ones.

This work was done over more than five years from 2018 to 2024, so this table was created from memory, and most of the costs are rounded to the nearest thousand dollars.

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Initial solar | $8,000 |

| More solar plus battery | $25,000 |

| Heat pump water heater | $8,000 |

| Induction stove | $2,000 |

| Electric vehicle | $45,000 |

| Heat pump HVAC | $17,000 |

| TOTAL | $105,000 |

As you can see, electrifying our lives wasn't cheap. Even with the incentives offered by local and national governmental organizations, we still paid nearly $100k to go green. Obviously, this isn't practical for most people. Fortunately, we did make a few mistakes that made this a bit more expensive than what most people will pay.

Mistakes and savings

The biggest mistake we made was adding solar to our garage in the initial installation. The problem is that we eventually wanted to add a battery in order to ensure we aren't hitting the grid. Well, the battery has to be connected to our house for it to be useful, but we added the solar to our garage, which is on a separate electrical panel. So we either had to trench out to our garage in order to connect the panels to our house, or we had to install a new solar setup on our house. The latter ended up being cheaper. We should have just installed our initial set of solar panels on our house.

The biggest cost on this chart is the electric car. We bought an Ioniq 5 because we thought that it had the best range at the price when we bought it. Still, you can get good used electric cars for less than half that cost. On Carvana, there are 2023 Hyundai Konas listed at under $20k. Generally, you shouldn't worry about range. Most people drive less than 40 miles a day, and modern electric cars will charge more than that overnight.

So the total cost here is high, even for California. If you eliminate the battery and install your initial solar setup correctly, then you can save $25k, bringing the total cost down to $80k. If you then buy a used EV, you can shave off another $25k, bringing the total cost down to $55k.

$55k is still a lot of money, but when you add government incentives, I think it's possible for anyone who owns a home.

Bay Area Oktoberfest Events Calendar 2023

Well, the 2023 Oktoberfest season for the Bay Area is as packed as ever. This year I decided I wanted to attend as many Oktoberfest events as I had the stomach for. So I did what any self-respecting beer nerd would do: I made a calendar, then I made a schedule. Here's the result of my labors. If you see me at these events, please come lift a glass with me!

20 questions you should answer before your senior fullstack programmer interview

I've been writing up some questions to help some friends prepare for interviews. I thought it might be worthwhile to share them here. I think that most senior fullstack developers should be able to answer these questions, and I think they're worth reviewing before you go into an interview.

20 fullstack engineer review questions

- What do the HTTP response codes beginning with 1-5 indicate?

- Name 5 different types of databases. Give examples of each.

- Name three different Chrome developer tools or extensions that you use for debugging. When do you use each? Why?

- What is the Big O access time for an array, a linked list, a hashmap, and a binary search tree?

- How does the schema differ between relational databases and document stores? When does this matter?

- Name three different types of caching that come into play in any web request.

- What is database sharding? Why does it matter? How does it differ between relational databases and NoSQL document stores?

- What is the difference between a traditional row-store database and a columnar database? Why would you choose one over the other?

- How fast are the fasts sorts we know about in Big O notation? Name one sort that is that fast.

- What is binary search? Can you walk through an example? When is binary search useful?

- What is the most complex operation to perform on a binary search tree? Why?

- What is a database index? When is it appropriate to use one? How are database indexes implemented?

- What is a DNS?

- What is a CDN? When is it useful?

- How does Java scale differently from JavaScript? Why?

- Name three frameworks for building websites. Which do you prefer? Why?

- What is vertical scaling? What is horizontal scaling?

- What are the security concerns that arise when using a package manager like npm?

- What is a serverless environment? What performance concerns arise when deploying a website using serverless technologies?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of a REST API versus a GraphQL API? Why would you choose one over the other?

Bonus questions

Some of these are more about your informed opinion than about being right or wrong, but I still think it's important to review them and have a prepared answer.

- Name three different cloud service providers. Which do you prefer? Why?

- What is your preferred IDE? Why?

- How do you determine when a feature can be used in a given browser?

- When is a key-value store a good choice?

- What is your favorite programming language? Why?

Project: Client-side web form

This post contains the second assignment in my free web programming course.

Project: Client-side web form

Forms are how users enter data on the web. When you register for a website, you enter your username and email into a web form. When you buy an item from a web store, you send your payment information using a web form.

Generally speaking web forms have input components on them like text boxes and dropdowns and buttons. But this isn't always the case. Web forms can be cleverly hidden using JavaScript and CSS.

Typically a web form submits data to a server, which processes that data and responds to the user with something interesting. For instance, you might submit your username and password and get back an authentication token that allows you to use the private portion of a website.

Requirements

I want you to build a single web page using html and javascript only.

It should have three things on it.

- A page title in h1 tags.

- A label that reads "title:".

- An input text box.

- A submit button.

When the button is clicked, the title of the page should change to the title entered by the user without reloading the page.

Also, the user input must validated. The user should be prevented from using dirty words like "MacOS" and "iphone". Don't let them use either of those words in any capitalization. If those words occur in the input, then a red error message should be displayed underneath the text box that reads "Please refrain from using dirty words such as 'MacOS' and 'iphone'.".

Extra credit

For extra credit, make the form beautiful using CSS. Be creative, but try to make something that a typical web user might like.

How to Debug a webpage in Chrome

In this post, I'm going to show you several ways to debug javascript in Google Chrome.

TLDR: Shift + ctrl + c

Open the javascript console using the shortcut shift + ctrl + c. That means, press all three at the same time. If you're on a Mac, use cmd rather than ctrl.

Inspecting an element to add new styles

Open the dom example that we wrote in What is the DOM?. In this post, we'll use that page to explore three ways to find out what's going on in a webpage. The code should look something like this.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>How to modify the DOM using JavaScript</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="post">

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

</div>

<script>

let blogPost = document.getElementById("post");

let copyrightNotice = document.createElement("p")

copyrightNotice.innerHTML = "Copyright " + new Date().getFullYear() + " by the author";

blogPost.append(copyrightNotice);

</script>

</body>

</html>

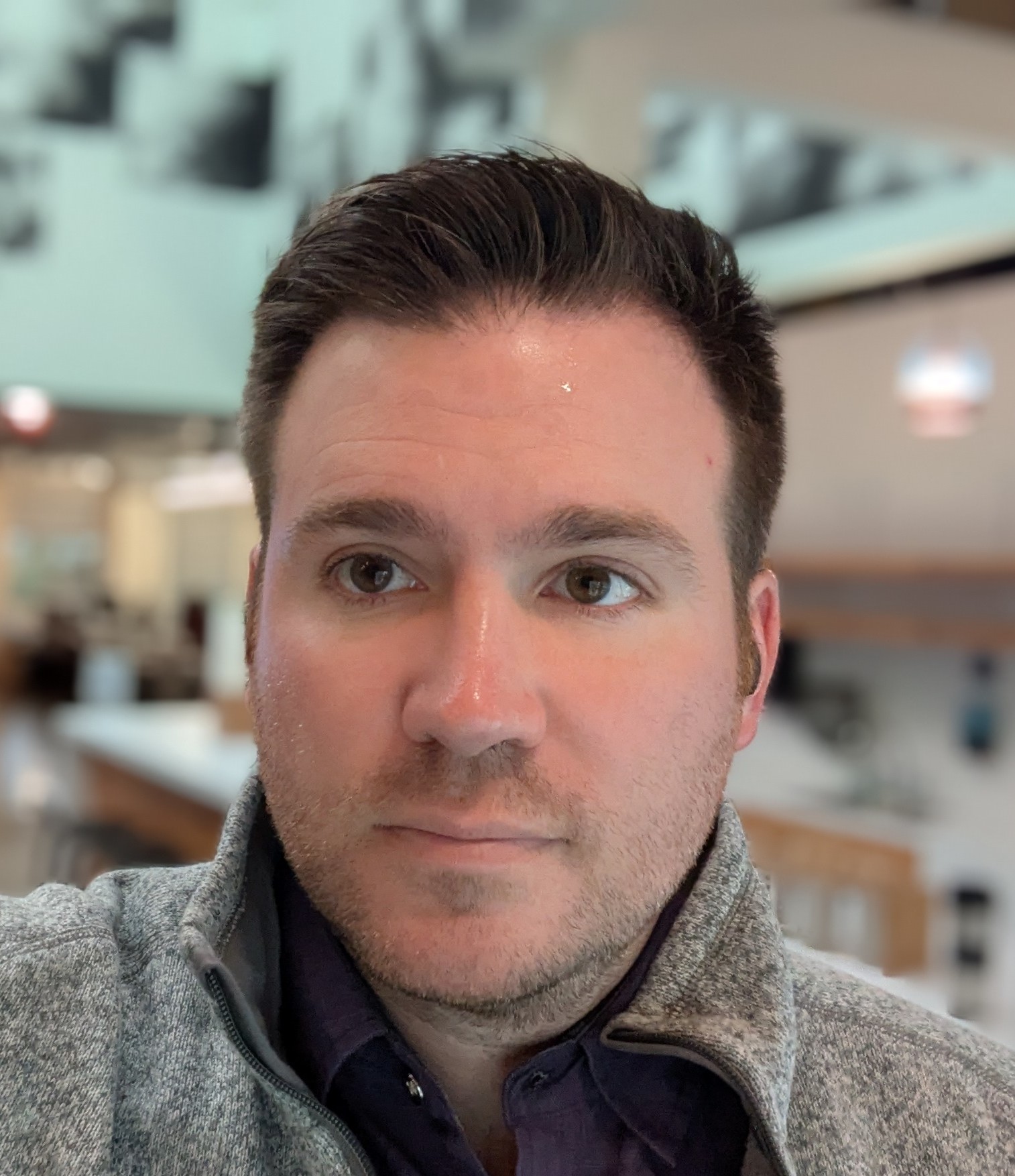

After opening it in Chrome, right click on the copyright notice, then click "Inspect" in the popup menu. The html for the element you clicked should appear in the "Elements" tab of the browser console. It should look something like this but there are several places where the console can appear.

Any time you are confused about an element, inspecting it is a good place to start. In the browser console, you should be able to see the html for the element, as well as any attached css. In fact, you can actually add new styles using the browser console. Notice in the "Styles" tab where it says "element.style" and there are empty braces. Any CSS you type in there will be applied to the selected element. Styles can also be toggled on and off. This can be exceptionally handy when trying to figure out why your page doesn't look quite right.

Go ahead and try it. Enter "font-weight: 800" into element.style. What happens?

Debugging using console.log

The most basic way to debug JavaScript is to put some console.log statements into your code, then open the console and see what they print. Calling console.log tells the browser to print whatever you pass in in the JavaScript console. You can console.log just about anything, but the web browser will format variables automatically if you put them in an object using curly braces.

So the following console.log call isn't very useful.

console.log('HERE!');

Whereas the following console.log call will allow you to examine the object passed int.

console.log({ confusingVariable });

Add the following line of code to the dom example after it sets the copyrightNotice variable.

console.log({ copyrightNotice });

Then reload the page and use shift + ctrl + c to open the browser console, or shift + cmd + c on a Mac. You may have to expand the window and click over to the tab that says "Console".

You should see something that says "{ copyrightNotice: p }", and if you expand it, then you should be able to see all the properties associated with that variable. It's not particularly useful in this simple example, but I use this technique virtually every day as a web programmer.

Debugging using the Chrome debugger

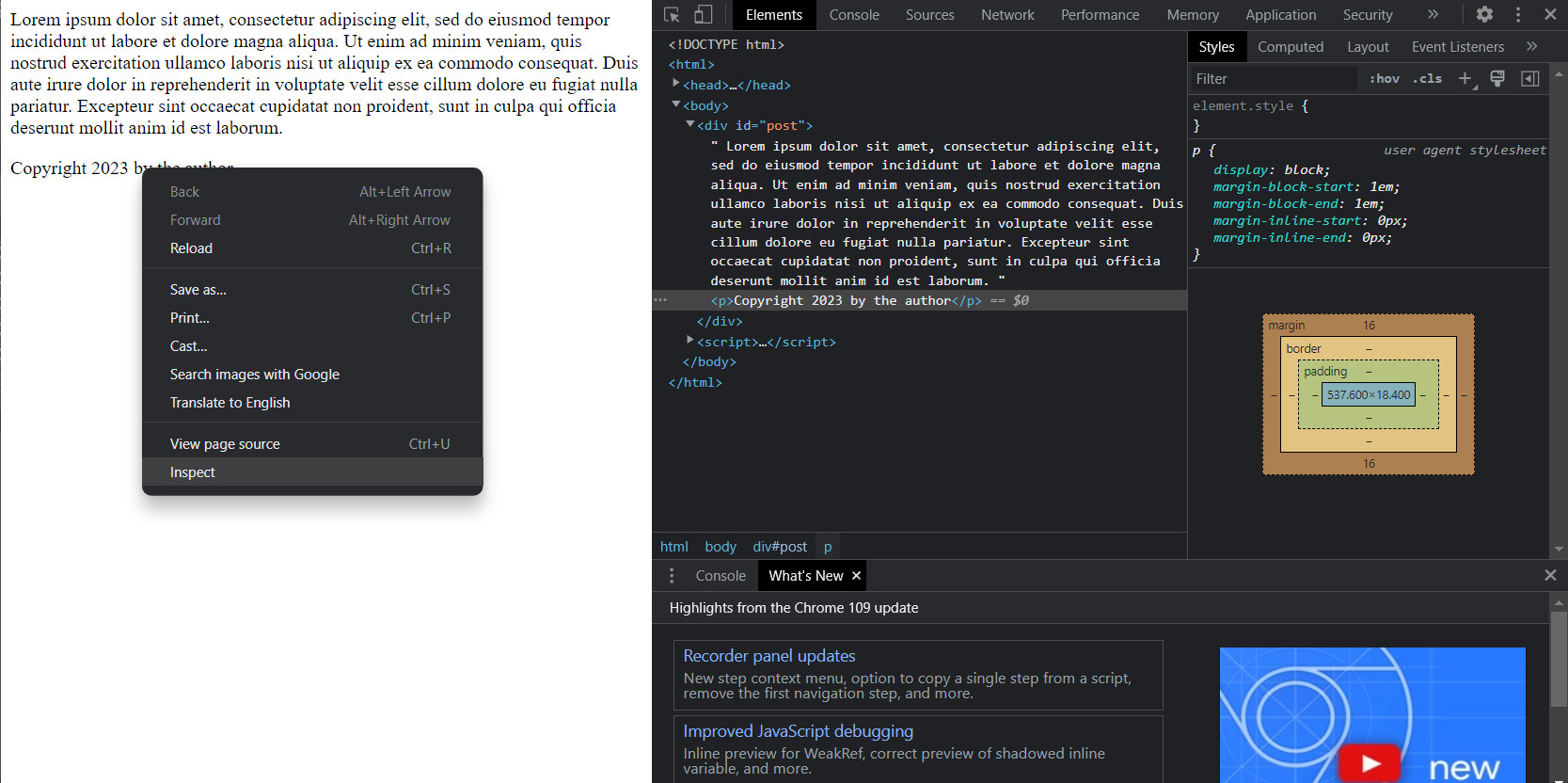

Keep the dom example open in Chrome. Then press shift + ctrl + c to open the browser console. Navigate over to the "Sources" tab. This tab is the built in debugger provided by Google Chrome. In this debugger, you can add breakpoints to your code, and the browser will stop at the breakpoints and allow you to examine the state of your code. It's okay if this looks very confusing. We don't need to do much with it.

There are three things you need to be able to do. First, you need to be able to navigate to the sources tab. Then you need to find the line numbers, because you need to click them. This is much more difficult in a typical web page that has many files. Finally, you need to know how to continue running the page after it stops at your breakpoints.

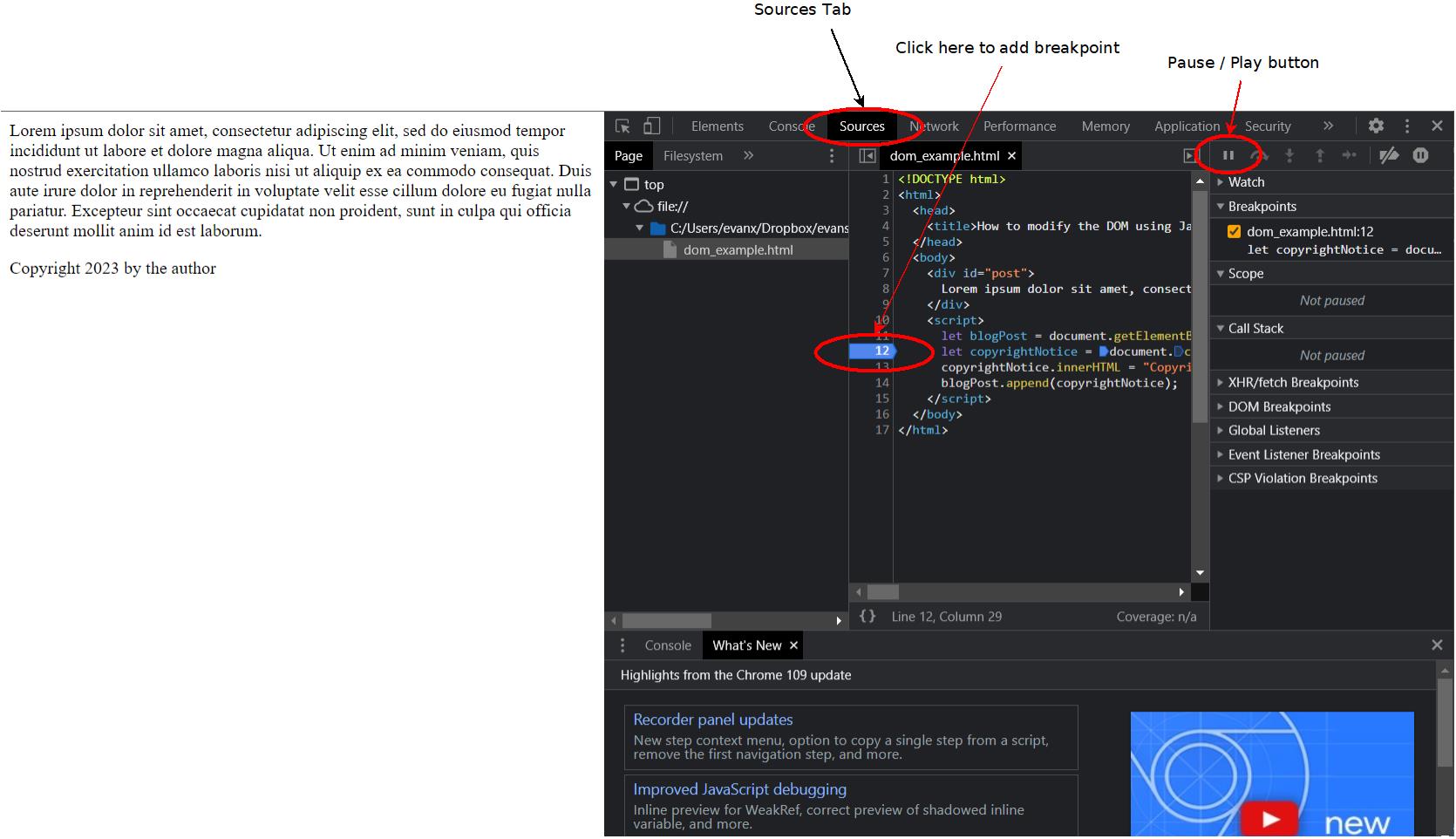

After you've opened up the page, click line 12 to set a breakpoint there. In this case, that code has already been run, so reload the page to make it run again. When you do so, you should see something like the following.

Notice the area that I've circled in that screenshot. It's where you can see the state of your code. All of your variables should appear there and you should also see their values. Notice that copyrightNotice is undefined in this case. That's because Chrome pauses before running the code at the line where you placed your breakpoint. If you place a breakpoint on the next line, then press the play/pause button to resume execution, the value for copyrightNotice should be filled in.

The Chrome debugger is a great way to examine the state of your code.