Neglected by Sam Hyde Harris

A few months back I saw an absolutely gorgeous painting come up for auction. The listing said it was by one of my favorite artists, Sam Hyde Harris. Unfortunately, the painting was unsigned, and it was listed at a pretty low price. Both of these things gave me pause while considering bidding on it. We all know how common fraud is in the art world. How could I be sure that this piece was genuine?

You can never be 100% sure that a piece is genuine. This is doubly true in an online auction where you can only see a handful of pictures of a piece. There were several aspects of this piece that made me think twice.

- It was unsigned

- It was a slightly unusual composition for the artist

- It was listed at a lower starting price than most pieces by Sam Hyde Harris

I took a risk on the piece anyway, and I managed to pick it up for a very reasonable price.

But that was only the beginning of the journey. Once I got the piece in my hands, I tracked down the Sam Hyde Harris expert Maurine St. Gaudens. Maurine literally wrote the book on Sam Hyde Harris, and she had the documentation from his estate to be able to conclusively prove whether a piece was by him or not.

Harris was a member of a group called the California Impressionists, so I wasn't surprised to find that Maurine was located in California. After speaking with her, I agreed to bring the painting down to her studio in Los Angeles, where she could authenticate it.

Maurine is an exceptionally interesting person. She is a tiny woman around age 70 with long brown hair down her back. She is an art conservationist, so her studio is absolutely overflowing with art. Her own collection hangs in every available spot on her walls, and the standing room is filled with paintings that she is working on.

Her collection includes dozens of paintings by California artists of the 20th century, and especially female artists about whom she also wrote the book.

When I arrived at her studio there was a very tall man wandering around as well. He turned out to be the noted Sam Hyde Harris collector Charles N. Mauch. When I handed the painting over to Maurine for authentication, Charles took me back to a garage and started showing me more paintings by Sam Hyde Harris. It turned out that they still had some paintings left over from his estate, and I was welcome to look through them and maybe even purchase a few (more on that in a future post).

Here's one of the beautiful pieces that Charles showed me.

When Chuck and I were done browsing the wonderful paintings in Maurine's garage I finally made my way back to her studio to hear the verdict.

Maurine was happy to tell me that the painting was a genuine Sam Hyde Harris. She was able to verify this in two ways. First, she found the painting in the inventory made by the estate when Harris died. Second, she had actually seen other versions of this painting. It turns out that Harris made multiple sizes of most of his paintings. He first made a sketch, then a very small study, then a 12x16 version, and finally a larger version. She had seen the larger version of my painting in the past, so she knew that mine was indeed legitimate.

She was also able to tell me, based on the inventory number, that the painting was created some time in the 1930s. So it's a relatively early easel painting for Harris, because at that time he was more focused on his career as an illustrator.

She authenticated the work by painting her mark on the front and signing the back. I drove it back to San Jose, where it now sits above my desk. I think it's one of my favorite pieces in my collection right now, along with the big Quincy Tahoma painting that I had restored.

Buying a painting like this at auction is always a bit of a risk, but in this case the risk paid off in spades. Not only did I get to hang a beautiful piece of California history on my wall, but I also got to meet some amazing people. It goes to show how a great piece of art can inspire and unite people even many years after its inception.

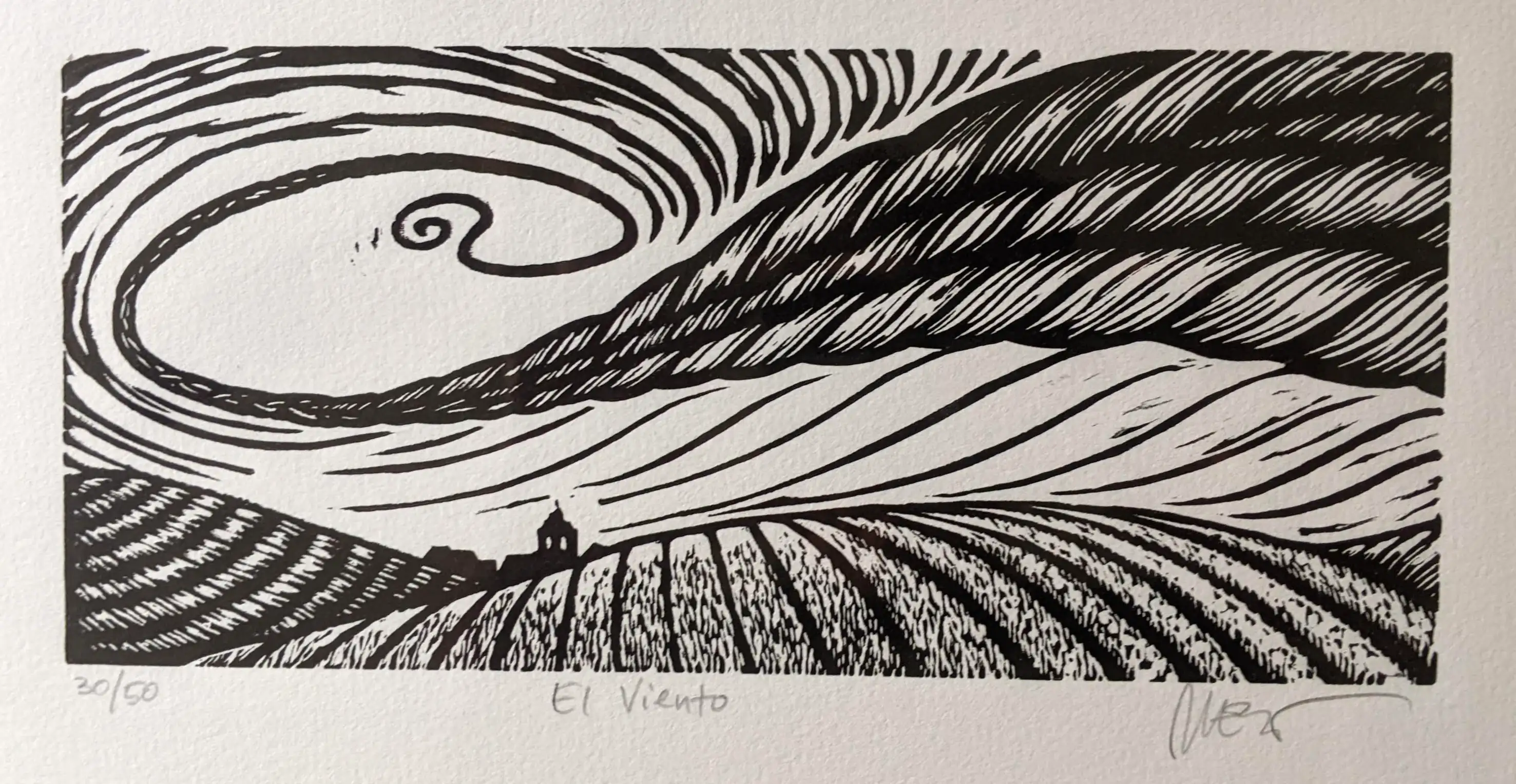

Discovering Bay Area linocut artist Melissa West

Yesterday I went to the SF Bay Area Printers' Fair and Wayzgoose. It was a fabulous and interesting event. I was so glad to see prints by so many local artists and printers. I enjoyed talking to everyone I met there, but I spent the most time at the booth of artist Melissa .

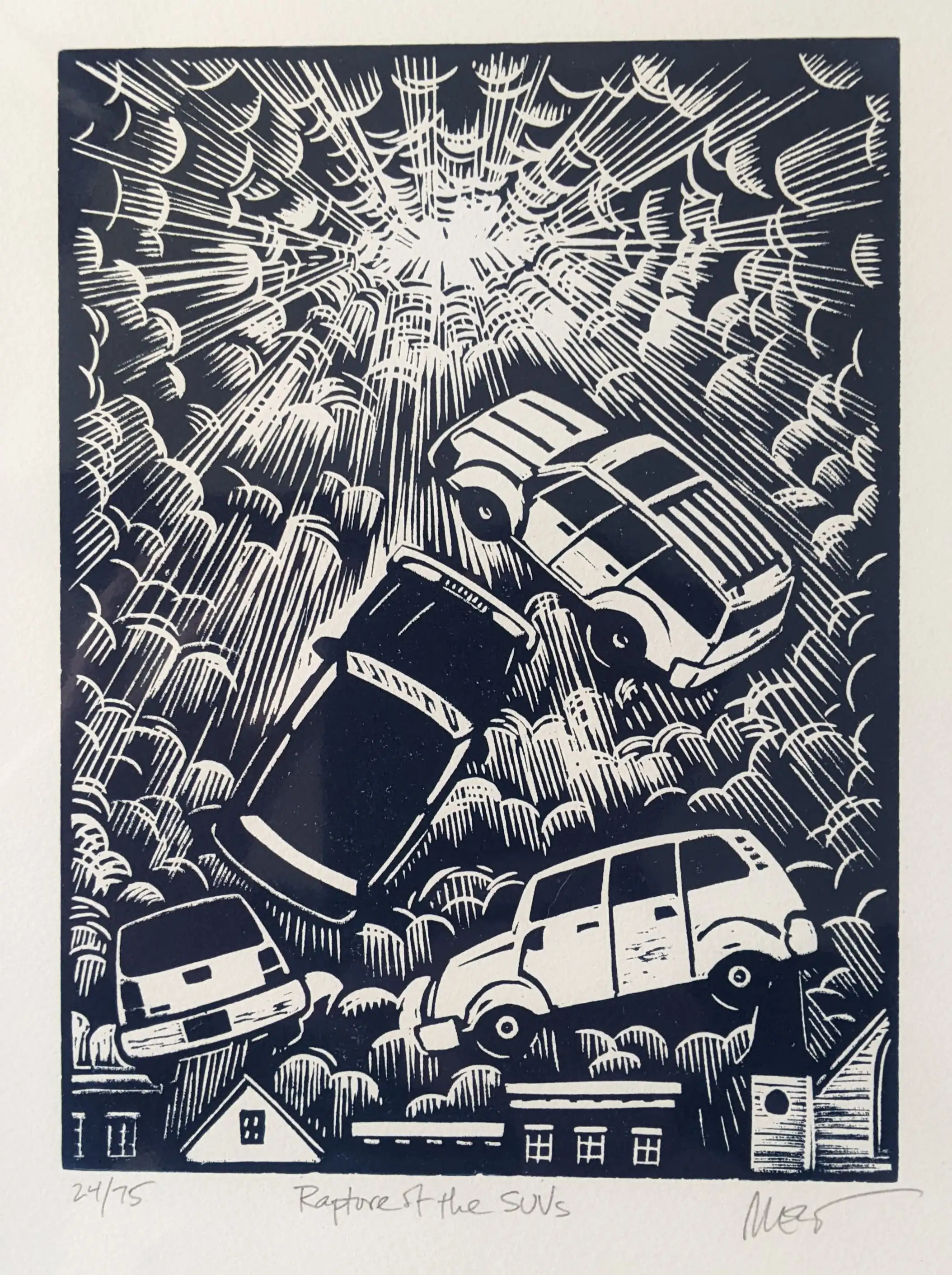

Most booths at the fair had around a dozen different prints to peruse, but I was blown away by Melissa's prolific output. Melissa must have had close to 100 unique pieces there if you don't count the 50 she did as illustrations in a book she was selling. Every piece was a handmade linocut with no digital processes involved. I spent time leafing through every single piece there.

Another thing that impressed me in West's work was her textual fluency. Her work incorporates numerous references to other works of art and culture. She had many pieces that mimicked style elements in medieval art, including a series about saints that portrayed figures in a Byzantine style. I particularly liked St. Christina the Astonishing.

I was also impressed simply by the quality of her work. Despite her massive output, every piece reflects a fluency with linocut that I see in very few artists. She has clearly devoted a lot of her life to the craft, and the time has been well spent.

As usual, I picked up a couple pieces to add to my own collection. I think this surreal landscape will look great next to my pieces by Sam Hyde Harris.

And this piece made me laugh. I think it will look good in my in-laws' house. Their house is adorned with artifacts relating to vehicles and travel.

I encourage you to check out Melissa West's work and pick up a print. Put something beautiful on your walls.

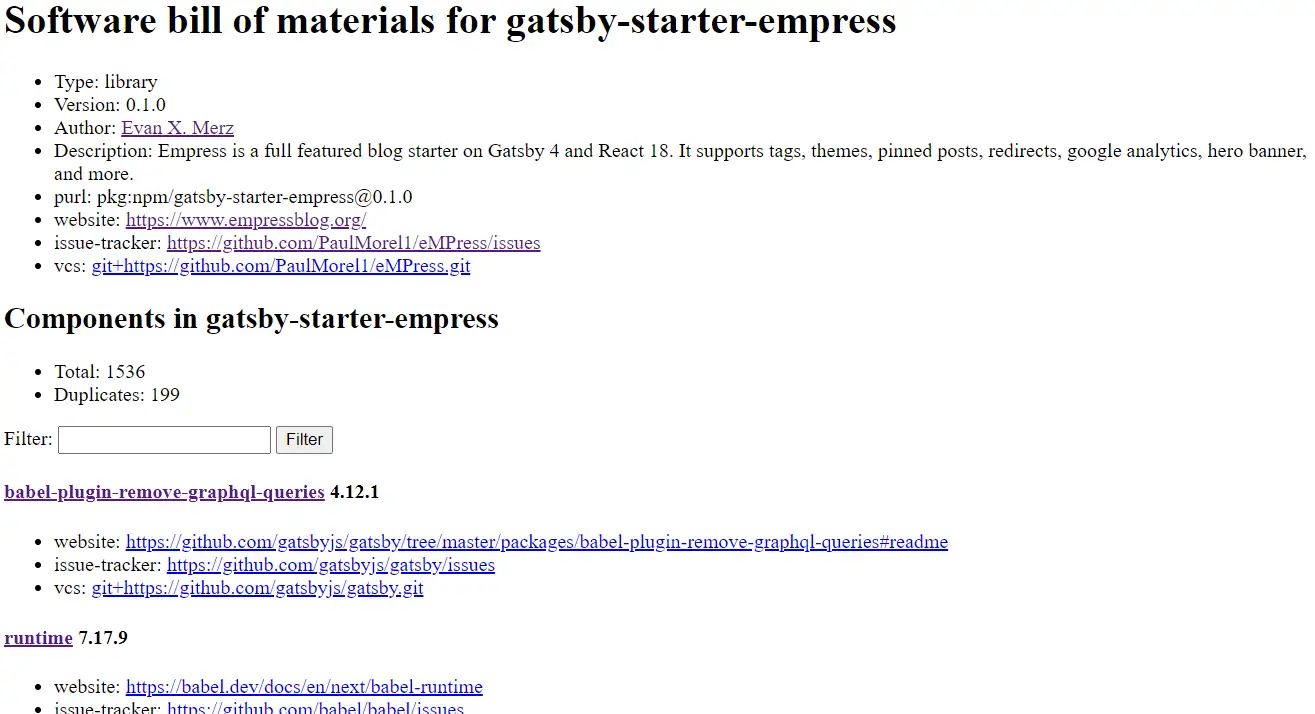

How to generate and view a node bill of materials

In this post, I'm going to show you how you can generate and view a software bill of materials (sbom) for a node.js project.

Why generate a bill of materials?

With the increasing attacks on the software supply chain by malicious actors such as foreign states and crypto miners, it's important to understand exactly what packages are in your node project. It's also important to understand the vulnerabilities in each of those packages. The tools in this tutorial link out to Socket.dev, which analyzes npm packages to find potential vulnerabilities. You may also want to consult with the National Vulnerability Database to see if any of your packages have known security holes.

Steps

- Install cyclonedx/bom. The CycloneDX SBOM Specification is a format for listing packages in a node library and any other software project. cyclonedx/bom is a tool for generating a sbom that conforms to the CycloneDX SBOM Specification.

npm install -g cyclonedx/bom

- Use npx to run it. Navigate to the directory of your node project and run the following. This tells the package to generate a bill of materials by analyzing the node_modules folder in the current folder and save the output to bom.json.

npx @cyclonedx/bom . -o bom.json

- Install viewbom. Viewbom is a simple npx tool I wrote that generates an html UI for navigating the bill of materials you just generated.

npm install -g viewbom

- Run viewbom on the sbom you created.

npx viewbom bom.json bom.html

- Open bom.html in a web browser. This should present you with a simple UI that shows you some basic statistics about your sbom and give you a way to search the packages in it.

It should look something like the following screenshot.

Or just use npm list --all

There's also a really easy way to generate a list of all packages in a project. There's an npm command for it.

npm list --all

If you don't need a searchable listing, then the built in npm command might be sufficient.

Why is software development so slow?

Why can't the developers move more quickly? Why does every project take so long? In this article I'm going to talk about what causes software development to slow down. This is based on my experience as a programmer and manager in Silicon Valley for over a decade, as well as conversations with other people in similar roles.

Is my team slow because...

First of all, I want to answer some questions that I've heard from managers.

- Is my team slow because we use PHP? No.

- Is my team slow because we use Java? No.

- Is my team slow because we use INSERT PRODUCT HERE? Probably not.

- Is my team slow because they don't understand web 3? No.

- Is my team slow because of a bad manager? Maybe, but if you've had multiple managers in there who haven't moved faster then this is unlikely.

- Is my team slow because they have or do not have college degrees? No.

- Is my team slow because we don't use agile? Probably not.

So then why is my development team so slow?

Now that we've gotten that out of the way, we can drill into what actually causes teams to move slowly. None of the reasons I've listed here are particularly technical. I tend to think that teams move slowly due to non-technical reasons.

They're estimating poorly

The most common reason why people think developers are moving slowly is that the estimates are poor. For one reason or another, developers are not spending the time, or creating the artifacts necessary to generate accurate estimates.

I once joined a small team where nobody ever wrote anything down. They would attend planning meetings where they would hash out the requirements, they would make up an estimate on the spot, then they would immediately break to start writing code. The stakeholders wanted to know why tasks never seemed to come in within the estimated time frame.

In my experience, it's necessary to generate multiple levels of plans to generate an accurate software development project estimate. You must begin with use-cases, then work through multiple levels of plans to reach units of work that can be estimated.

Here's how I break down a project to make an accurate estimate:

- Write all requirements down in plain language. This can be in the form of use cases, or user stories, or any top-level form that anyone can understand.

- Talk through what an acceptable solution would look like with other developers.

- Break that solution into individual tasks using a tool like JIRA.

- Estimate those tasks.

- Add a little extra room for unknowns, debugging, integration, and testing.

- Add up the final estimate.

There are multiple ways to execute each of these steps, but that's the general flow for all successful software development estimation that I've seen in my career.

Technical debt

Another big reason why a team might be moving slowly is tech debt. Tech debt happens to every project when the company tries to move quickly. It happens because solutions that can be implemented as fast as possible are usually not scalable to future use cases that the developers can't anticipate.

I once worked on a web development team that needed to make the list pages faster on an e-commerce website. The list pages were slow because the server was delivering a massive payload containing every product on the list page then filtering and sorting was done client side. That's easy to fix right? Just serve the first page of products, then serve the next when the user scrolls down. But to do that, we must add server side sorting and filtering because the list will be different for different combinations of sorts and filters. But to do that, we must have products stored in some sort of database, and this team was only using a key-value store at the time. That's how tech debt can be problematic. In that scenario, it would take months to solve that problem in a scalable way.

Ultimately, we found a different solution. We delivered the tiniest possible payload for each product, which achieved a similar end goal while side-stepping the tech debt. But that tech debt was still there, and would still be a problem for many related projects.

There is no silver bullet for solving tech debt. In my career, the best way I've found to deal with tech debt is to reserve one developer each sprint to iteratively move the project closer to what the team agrees is a more scalable solution.

Interpersonal conflict

The single biggest thing that slows down development teams is interpersonal and interdepartmental conflict. Maybe a manager is at odds with a team member, or maybe two team members see their roles very differently. If two people working on one project have different views about how to execute that project it can be absolutely crushing.

I think that proactively avoiding and addressing conflict is the single thing that can instantly help teams move faster. The most staggeringly successful group of techniques I've discovered for doing so is called motivational interviewing.

Motivational interviewing is a way of communicating with peers, stakeholders, and direct reports that allows two people to agree to be on the same team. It's a way of building real rapport with people that allows you to build successful working relationships over time. Specifically, it's a way of focusing a conversation on talk that meaningfully moves both parties toward a mutually acceptable solution.

I strongly recommend Motivational Interviewing for Leadership by Wilcox, Kersh, and Jenkins. To say that that book changed my life is an understatement.

Unclear instructions

The final category of issue that slows down development teams is unclear instructions.

I once worked for a person who was very fond of sending short project descriptions over email and expecting fast results. One email might read something like "I want to be selling in Europe in one month", another might say "I want to be able to hold auctions for some of our products."

It IS possible to work with such minimal instructions. It falls upon the development team to outline what they think the stakeholder wants, develop plans based on that outline, then execute based on those plans.

The problem with working from minimal instructions is that no two people see the same problem in exactly the same way. Say you are developing that auction software. Many questions immediately arise. Who can bid on the auctions? Is the auction for many products or just one? Does the product have selectable options, or are they preset? Are bids visible to other customers? How do we charge the user for the item if the final bid exceeds what is typically put on a credit card?

If the stakeholder isn't able to answer those questions early in the process, then it may go significantly astray. If the development team doesn't understand the instructions, then they may waste days or weeks pursuing irrelevant or untimely work. If the stakeholder is going to give such vague instructions then they must address questions in a timely manner or risk tasting time.

In conclusion

So why is your development team so slow? I've laid out the four common causes that I've seen in my career.

- Poor estimates

- Tech debt

- Interpersonal conflict

- Unclear instructions

If you have something else to add to this list, then let me know on Twitter @EvanXMerz.

Sam Hyde Harris: Seeing the Unusual at Casa Romantica

I recently attended the exhibit Sam Hyde Harris: Seeing the Unusual at Casa Romantica in San Clemente, California. The exhibit was curated by Maurine St. Gaudens and Joseph Marsman and brought together around 60 pieces by Sam Hyde Harris in just two rooms on the lovely Casa Romantica estate.

Sam Hyde Harris is mostly remembered by collectors today as an active member of the California Art Club who produced hundreds of beautiful landscapes of California in the early 20th century and taught numerous students who went on to great careers. He was also a member of a group called the California Impressionists.

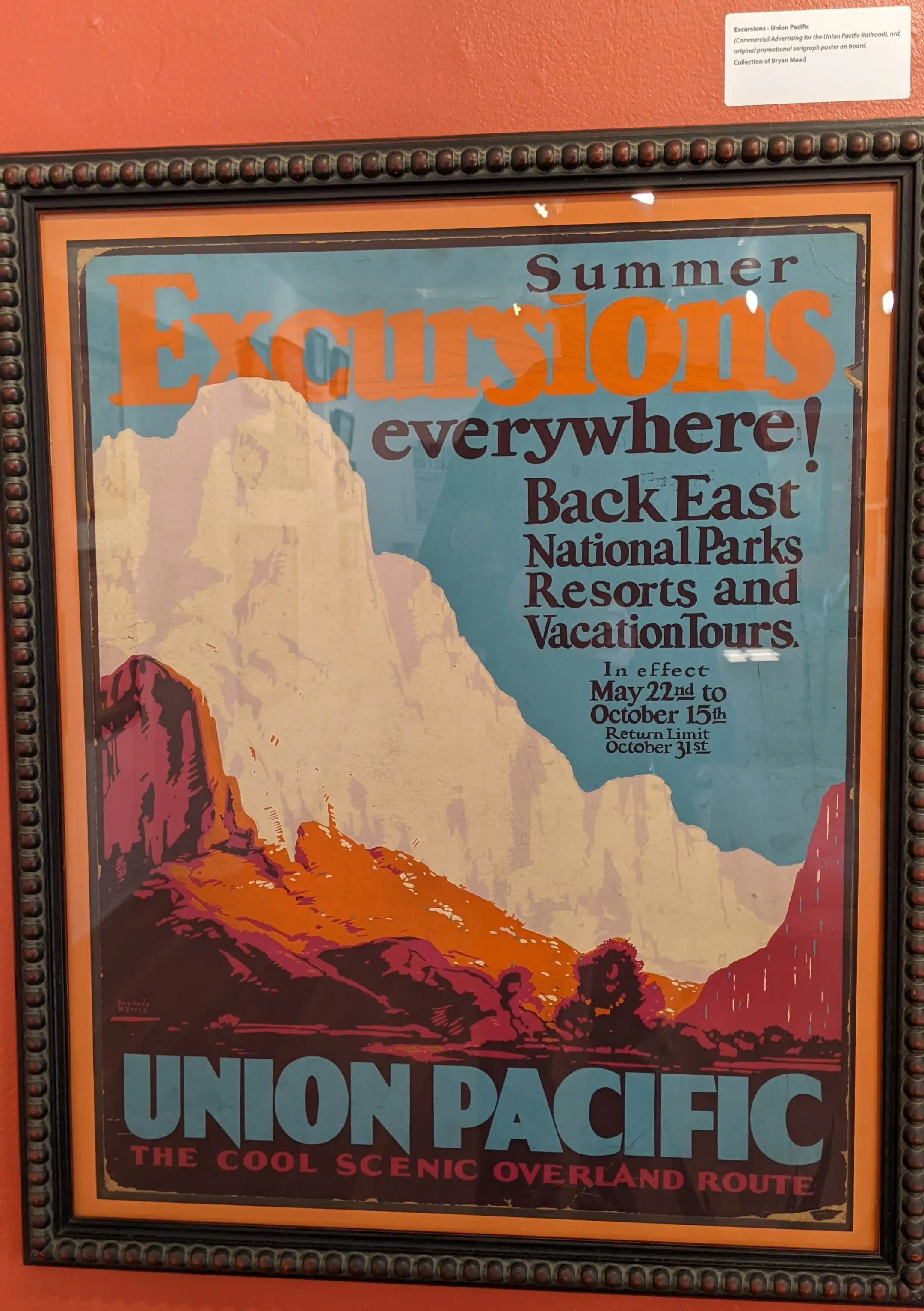

The focus of this exhibit was introducing a modern audience to the massive volume of commercial work he produced. This includes numerous posters for companies such as Union Pacific and the Santa Fe Railroad, as well as advertising pieces for local businesses and theater companies.

Here's the Curator's Statement from Maurine St. Gaudens.

Sam Hyde Harris, Seeing the Unusual explores the diverse oeuvre of this noted twentieth century California artist. Although widely known for the fine art compositions, few people realize the extent of Harris' commercial advertising work. Harris' designs shaped the consciousness of early to mid-twentieth century consumers and travelers. I really was quite surprised that so little attention had been paid to Harris the commercial artist. This exhibition explores this complex aspect of the artist's career.

My personal association with Sam Hyde Harris actually began more than thirty years ago when I was contacted by Harris' widow, Marion Dodge Harris, to catalogue the artist's estate. In the process I discovered examples of work the artist had created for a who's who of clients, not only in California, but across the western United States and nationally. It's the commercial work that today represents an historical record of product lines and services that were a part of everyday life from the 1920s - 1950s.

On a national level, Harris had a long and highly creative relationship with the railroad industry, specifically the Santa Fe, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific rail lines. His iconic Art Deco themed Southern Pacific's New Daylight poster has become one of the most recognizable images of this art form and one that has become highly praised by railroad and design enthusiasts alike.

Unfortunately, over the years, as is common with many commercial artists, their work has gone unaccredited, and Harris is no exception. Although, with new research and recent descoveries, this oversight is now being corrected, and Harris' commercial designs are being recognized by a new generation of historians.

Harris' commercial work wasn't the only thing in the exhibition, though. There were plenty of paintings of the subjects for which he was most famous, including boats in harbor, and the Chavez Ravine before it was developed.

I spent an hour poring over every piece in the exhibit. Many of the pieces came from the collection of Charles N. Mauch, including several massive paintings that became his most famous posters. I particularly enjoyed seeing the different stages of the Taxco Mission poster produced for Southern Pacific. Through a sketch, a painting, and a print of the final poster, visitors could see the complete evolution of one of his commercial pieces.

I only recently became a fan and collector of work by Sam Hyde Harris, and I was glad to have the opportunity to see so much of his work in one place. I was also glad that this less well-known California artist was being brought to new audiences in the 21st century.

Sam Hyde Harris: Seeing the Unusual ran from November 19, 2021 through February 27, 2022.