How to set up stable diffusion on Windows

In this post, I'm going to show you how you can generate images using the stable diffusion model on a Windows computer.

How to set up stable diffusion on Windows

This tutorial is based on the stable diffusion tutorial from keras.io. I started with that tutorial because it is relatively system agnostic, and because it uses optimizations that will help on my low powered Windows machine. We only need to make a few modifications to that tutorial to get everything to work on Windows.

Steps

- Install python. First, check if python is installed using the following command:

python --version

If you already have python, then you can skip this step. Otherwise, type 'python' again to trigger the Windows Store installation process.

- Install pip. You can install pip by downloading the installation script at https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py. Run it using the following command.

python get-pip.py

- Enable long file path support. This can be done in multiple ways. I think the easiest is to run PowerShell as administrator, then run the following command:

New-ItemProperty -Path "HKLM:\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\FileSystem" `

-Name "LongPathsEnabled" -Value 1 -PropertyType DWORD -Force

- Install dependencies. I had to manually install a few dependencies. Use the following command to install all needed dependencies.

pip install keras-cv tensorflow tensorflow_datasets matplotlib

- Save the code to a file. Save the following code into a file called whatever you want. I called mine 'stable-diffusion.py'.

import time

import keras_cv

from tensorflow import keras

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

model = keras_cv.models.StableDiffusion(img_width=512, img_height=512)

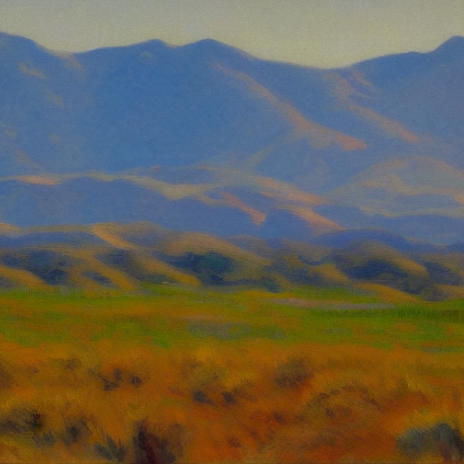

images = model.text_to_image("california impressionist landscape showing distant mountains", batch_size=1)

def plot_images(images):

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 20))

for i in range(len(images)):

ax = plt.subplot(1, len(images), i + 1)

plt.imshow(images[i])

plt.axis("off")

plot_images(images)

plt.show()

- Run the code.

python stable-diffusion.py

- Enjoy. To change the prompt, simply alter the string that is fed into 'model.text_to_image' on line 8. Here are my first images created using this method and the given prompt.

Initial Experiments with Make-a-Scene by Meta

Last week Meta announced their entry into the field of artifical intelligence image generation. Their new tool is called Make-a-Scene and it takes both an image and a line of text as prompts. It's a more collaborative tool than some of the other image generators made by other companies. A person can sketch out a rough scene as input, then use text to tell Make-a-Scene how to fill it in.

Make-a-Scene isn't yet open to the public, but as a Meta employee, I was able to get my hands on it early. In this post, I'm going to show you my first experiments with Make-a-Scene, and you can see how it compares to the other image generation tools.

As a lover of California landscapes, and a collector of the painters known as the California Impressionists, I had to start by trying to generate some California landscapes. I drew an image with a sky, a mountain, a river, and a fence. Then I gave it the prompt "an impressionist painting of california". This image shows the input along with four generated images.

I particularly liked the first two images.

As you can see, Make-a-Scene tries to follow the image input as closely as possible, and it's able to interpret the phrase "impressionist painting" in many different ways.

Next, I fed it the much more specific prompt of "Emperor Palpatine training Anakin Skywalker". As you can see from the generated images, it struggled much more to understand both my poor drawing, and the very specific text prompt.

You can see how my drawing led the AI astray in the generated images. I included lightsabers in sections of the image labeled as "person" so Make-a-Scene added some funky looking arms onto the people. Interestingly, it didn't necessarily understand who the fictional characters were, but it knew that they were soldiers.

For my last experiment, I went back to something more generic. I though about the type of images that marketers might need. I drew a picture of a person-shaped blob holding a spoon-shaped blob, and gave it the prompt "a woman eating breakfast". The results are trippy, but interesting.

The first image it generated looks almost like usable clip art.

Overall, I think Make-a-Scene is interesting and fun. I think, even in this early state, it has some real possibility for generating art in some situations. I think it would be particularly good at creating trippy art for album covers or single artwork on music streaming sites. I also think it could be useful for brainstorming visual ideas about characters, concepts, and even fiction. I hope that Meta opens it up to the public soon.

A Sophisticated Provincial by Margo Alexander

There is very little information available online about the California artist Margo Alexander, and that is a shame. I was recently fortunate enough to pick up a small and interesting piece by her and I wanted to make sure to share what I knew about her online. I don't know the title of the piece, but it's one from a series she called Sophisticated Provincials, and they are still widely available at reasonable prices on ebay.

Margo Alexander was a muralist and printer who ran a large art studio in California in the first half of the 20th century. Here's what it says about her in Emerging from the Shadows.

In Los Angeles, she established her reputation as a muralist, creating custom murals for private homes and public buildings. As in her oil and watercolor paintings, her mural subjects included figurative, landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes. She also designed fabric, china, and table linens. By the early 1940s, she employed six full-time artists at her Los Angeles studio to assist with mural commissions and with her more commercial production of serigraphs, which she called "Sophisticated Provincials," which were created using a hand reproduction technique she developed that attempts to retain the spontaneity of an original painting. These were simply signed "Margo."

What I think is interesting about Alexander is that she was commercializing screen prints in a way very similar to what Andy Warhol claimed credit for decades later. She was pumping out these small, semi-handcrafted works that were designed for the mass market. It's true that these small, quaint scenes haven't withstood the passage of time as well as Warhol's, but I still think she needs to be put in the same context as Warhol.

Here's the piece I picked up for $8 on ebay. It's only about three inches square.

Here's what it says on the back, if you're having a hard time reading the small print.

Widely recognized for the dash and color of her original paintings and murals, this popular western artist strove to develop a hand-reproduced technique retaining all the piquant spontaneity of her prized originals.THIS, with the support of her associates, Ann Bode and a talented staff, in the seclusion of her tree-covered old-world studio, she has achieved and proudly presents herewith her original hand-replica of...

I can't read what was originally in the box at the bottom, so I can only speculate at the title.

I hope that by putting this online I can preserve some memory of an artist who was successful enough to run her own store in Los Angeles for decades.

Goodbye to Zadie Smith, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Aubrey Beardsley

I am definitely a book hoarder. I love my books. I love the smell of the paper. I love the sound the spine makes when you open it for the first time. I love the way a bookmark looks when it's peering out from the middle of the book, keeping your spot for you.

It's hard for me to let go of books, but since I live in a relatively small house in California, I have to make a habit of getting rid of books every few months. I usually take them down to a Little Free Library, or to Goodwill.

But I've decided to start blogging about the books I donate, so that I can remember them on the internet, even if they aren't on my bookshelf.

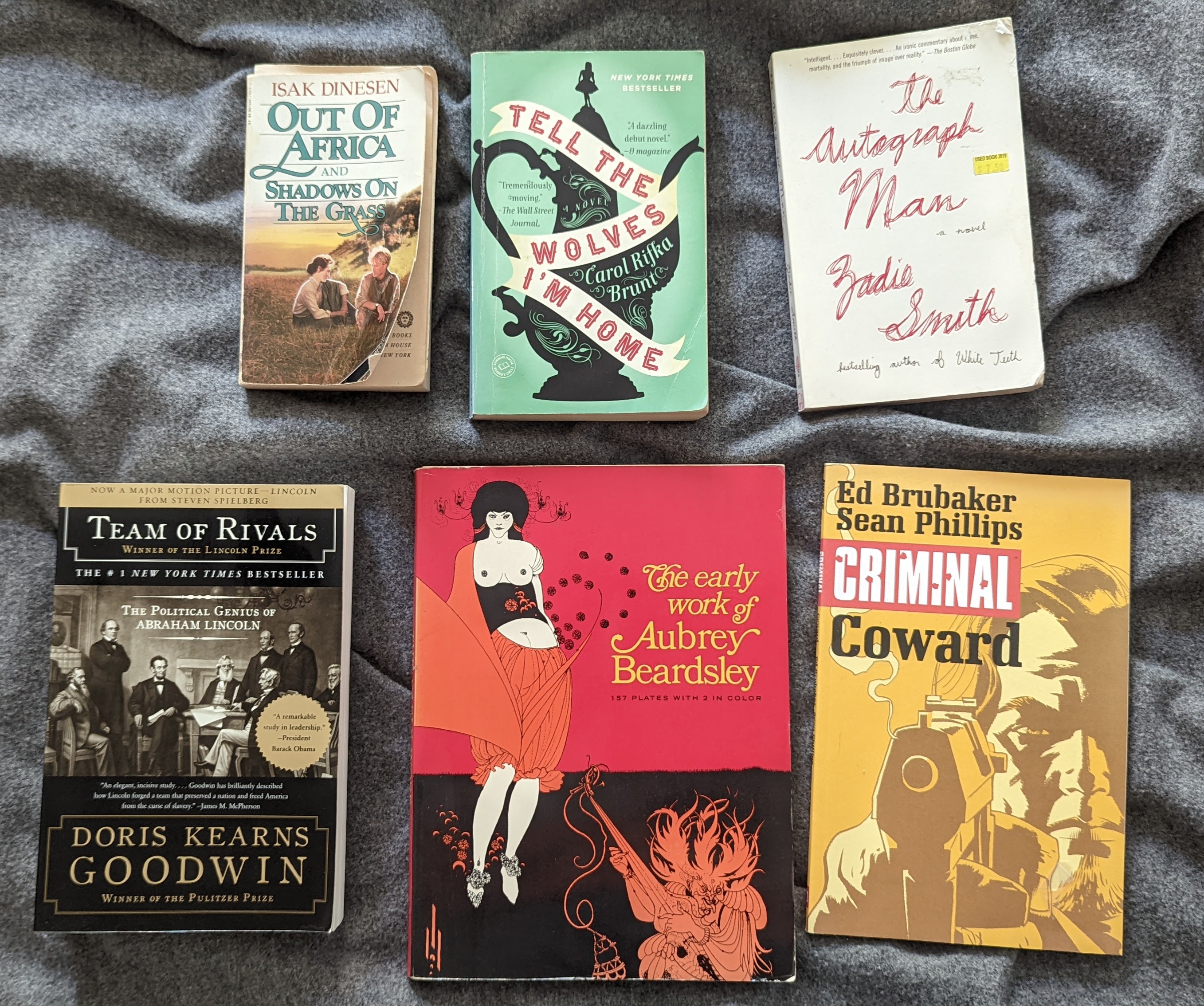

Here are the books I'm saying goodbye to today.

Out of Africa by Isak Dineson

I love the way Isak Dineson writes. Her words ache with empathy and bittersweet longing for things she can never possess. Of course, she's writing about her time as a colonizer, and that throws a disagreeable shade over her work. But her memoir of colonial Africa in the early 20th century is still marvelous and fascinating.

I pulled this copy out of a Little Free Library in my neighborhood, and it wasn't in very good condition when I found it. The cover is battered, and some pages are falling out. Still, I think it will serve a few more readers, so I am taking it back to where I found it.

Tell the Wolves I'm Home by Carol Rifka Brunt

This book made me cry at the end. I loved it. My wife gave it to me after she finished it.

I love media that is set during the AIDS crisis. Maybe it's a little dark to admit that, but I just love the gay art scene of the 1980s in New York and London. As pointed out by Rent, there is a romantic pathos about making art and dying for love, and this book captures it so well.

The Autograph Man by Zadie Smith

The Autograph Man is not my favorite book by Zadie Smith, but nothing she writes is bad. I like the way she gives us these windows into subcultures that feel so authentic. In this case, it's a window into the life a Jewish man who buys and sells autographs.

My wife read this book, then passed it on to me.

Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin

I was gifted this book for Christmas a few years ago. Team of Rivals is truly one of the great books about Abraham Lincoln and The Civil War, and there are thousands upon thousands of books on those topics.

Still, I think this book could have been 150 pages shorter and achieved the same thing. I'm not sure that hundreds of pages about the early lives of Lincoln's cabinet members really informs the story about their decisions during our greatest national crisis. It took me nearly two months to get through this book, but I'd still recommend it to history buffs.

The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley

I went through a brief love affair with Aubrey Beardsley's work, and it still amazes me to see illustrations produced in the late 19th century that were so influential on later art. Many of Beardsley's illustrations look like they would be more at home in the psychedelic posters of the 1960s San Francisco rock scene. I would love to be able to pick up one of his original prints, but the market is saturated with reproductions and fakes.

I picked this book up for two dollars at an estate sale. I hope it introduces someone else to the brief career of a very influential illustrator.

Criminal Volume 1 by Ed Brubaker

Most comicbook readers will recognize this one. I've enjoyed a lot of Brubaker's work, but this one just didn't pull me in, despite being heavily recommended.

Save the planet. Wear a hat

One of the odd sacrifices of our modern way of life is hats. Hats used to be everywhere. Everyone wore a hat every day. Just look at this 1940 painting by Jacob Lawrence. Do you see anyone not wearing a hat?

Why did everyone wear a hat? Because their hair was a greasy mess. Today we tend to shower more often than our ancestors, so we've dropped some of the layers of clothing that they preferred, including hats.

People still wear functional hats. Baseball players need to shade their eyes from the sun. Construction workers and football players need to protect their fragile skulls.

People also wear hats that form part of their uniform. The pope's hat is particularly famous, and the Queen's Guard wouldn't look right without their characteristic bear skin hats.

But outside of the occasional horse race, nobody wears big, fancy hats any longer. Like when was the last time you saw someone wearing hats like the ones worn by the Duke and Duchess of Urbino in this dual portrait by Piero della Francesca?

I think I'd look good in that giant red hat.

And anyway are we really better off showering every day? Between the dry skin and the lack of hats, I'm not entirely convinced.

Plus, showers are a massive waste of water and energy. I know I don't need to turn the hot knob all the way up, but I can't help myself. So the planet would be better off if we skipped a shower now and then.

And that would be much easier to do if I owned a few good hats. One artist who definitely liked a fancy hat was Rembrandt van Rijn. I had a hard time picking just the right self-portrait to feature in this post, but I think this hat with two feathers down the front would turn a few heads if someone was bold enough to bring it back.

So if you are a connoisseur of haberdashery, and you care about the planet, then do yourself a favor; buy a fancy hat and skip the shower.